We need to broaden the way we look at new fossil fuel infrastructure

When the Rhode Island Energy Facilities Siting Board (EFSB) considers the licensing for a new fossil fuel burning power plant, it weighs several factors, as is mandated by law. The EFSB board members must weigh the economics of the the proposal: Will the potential power plant provide power at a low or at least competitive cost to energy consumers? Will

November 28, 2018, 9:13 am

By Steve Ahlquist

When the Rhode Island Energy Facilities Siting Board (EFSB) considers the licensing for a new fossil fuel burning power plant, it weighs several factors, as is mandated by law. The EFSB board members must weigh the economics of the the proposal: Will the potential power plant provide power at a low or at least competitive cost to energy consumers? Will it do more harm, as in harm to the environment, than good?

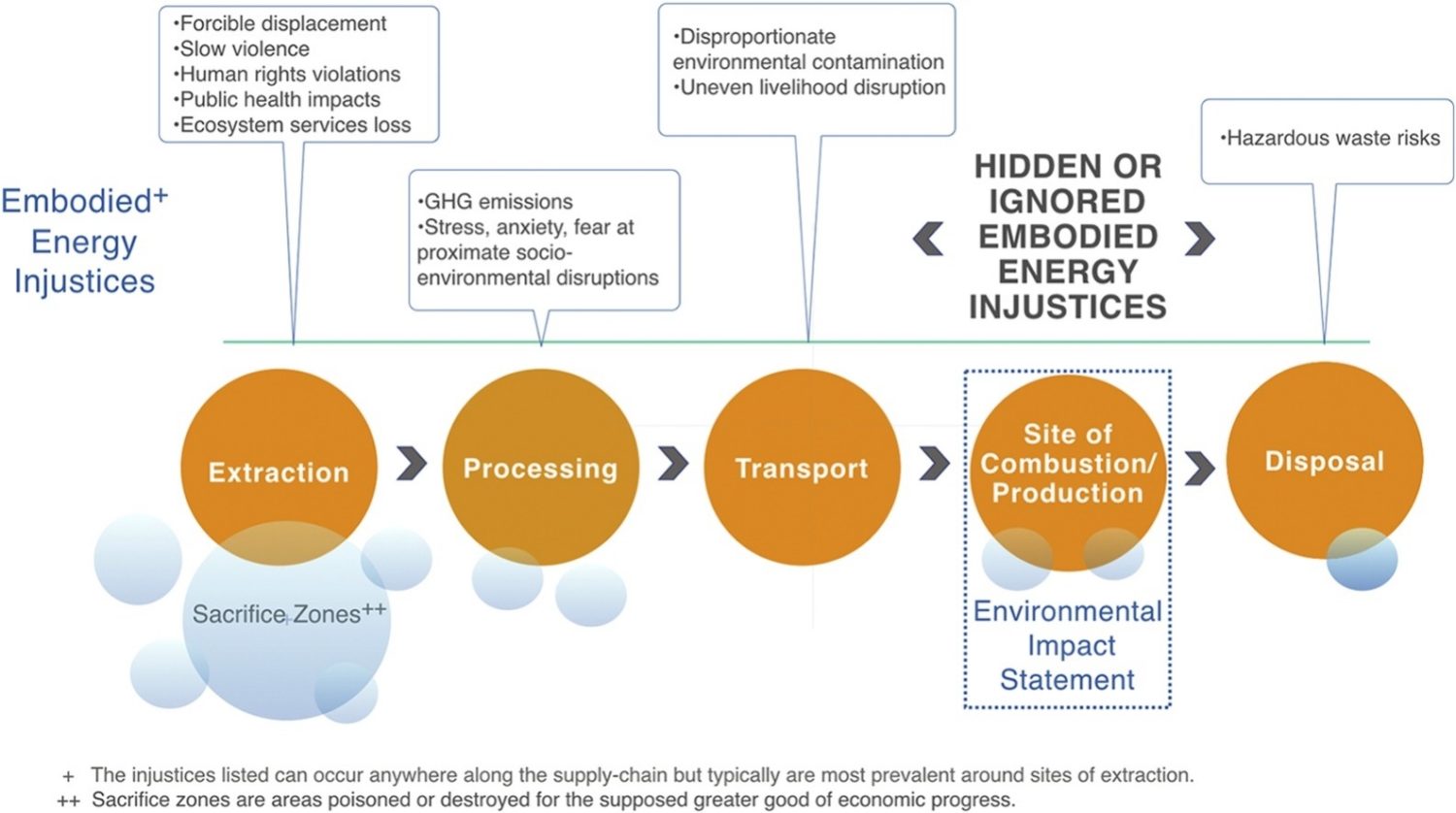

In weighing these factors, only local impacts are considered. For instance, air quality, wildlife disruption, and other ecological impacts are only considered within Rhode Island (and perhaps just over the border) and often only in the immediate area of the plant. Contrary to this, a new paper, “Embodied energy injustices: Unveiling and politicizing the transboundary harms of fossil fuel extractivism and fossil fuel supply chains” from Dr Noel Healy, Jennie C Stephens and Stephanie A Malin, argues that the justice implications, “especially for distant communities further up or down the energy supply chain,” need to be taken into consideration, writing:

“Energy decisions have transboundary impacts. Yet Environmental Assessments (EAs) and Environmental Impact Statements (EISs) of large-scale energy infrastructure, including distribution networks and pipelines, shipping terminals, and rail and trucking networks intended to transport fossil fuels to markets, rarely consider the direct and indirect greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of such infrastructure linked with either upstream extraction or downstream consumption. Moreover, the justice implications—especially for distant communities further up or down the energy supply chain (e.g. “sacrifice zones”;)—are routinely overlooked or deliberately ignored. The net effects of this analytical gap are incomplete considerations of climate impacts, and omissions of socio-environmental justice implications of energy decision-making.”

It is easy in Rhode Island to see the environmental injustices being perpetrated on the residents of Providence’s south side with the recent approval of National Grid‘s liquefaction facility in the Port of Providence and the ongoing degradation of the environment there. Residents endure the highest rates of asthma in New England, and fear potential disasters in the form of a tanker truck spillage, bomb train derailment and pipeline explosion, among others, that are becoming frequent occurrences in the community.

Less easy to see are the effects at a distance, such as the forcible displacement of people living near sites of natural gas extraction, with the commiserate health implications on the people there, not to mention the violence, human rights violations and environmental impacts in places such as Standing Rock and elsewhere.

The authors of the paper identify five places along the energy supply chain where these environmental injustices take place; Extraction, Processing, Transport, Production and Disposal. Each link in this chain is ripe for social, economic, environmental and health injustices, and each link gives rise to “sacrifice zones.” Sacrifice zones are defined in the paper as “areas poisoned or destroyed for the supposed greater good of economic progress.” In Rhode Island, there are literally hundreds of such sites. We call them Brownfields, areas contaminated by controlled, hazardous and/or petroleum-based substances.

The authors of the new study conclude that:

“Energy production, consumption and policy-making decisions in one place can cause hidden but harmful, multi-dimensional, socio-environmental injustices in others. Expanding the conceptualization of energy justice to include transboundary responsibility and impact invites new approaches to corporate accountability in the fossil-fuel industry. It shifts attention upstream to the extraction of fossil fuels, placing a new focus on traditionally overlooked elements of the fossil-fuel supply chain (e.g., sacrifice zones) and on the state and non-state actors that organize, invest in and benefit from the extraction, processing and distribution of fossil fuels.”

For environmentalists and activists combating new and unneeded fossil fuel infrastructure in their region, the authors suggest that,

“Connecting local energy struggles with distant transboundary social impacts creates opportunities for new solidarity movements. Disruptive political action across different jurisdictions can expose and weaken the fossil-fuel industry’s narratives that claim commitment to socially responsible activity. The concept of embodied energy injustices can be used to counter corporate greenwashing designed to redirect public attention away from contentious debates about extraction injustices and the fairness of rent distribution, and to perpetuate the slow violence of polluted waterways, degraded lands and social unrest long after extraction ceases.”

See:

Blood coal: Ireland’s dirty secret

What Terrible Injustices Are Hiding Behind American Energy Habits?

UpriseRI is entirely supported by donations and advertising. Every little bit helps:

![]()