Sex Workers enter the national landscape as presidential candidates consider sex work-study

“We passed these laws without even considering [consensual sex workers’] voices,” said United States Representative Ro Khanna. “They didn’t get to testify in Congress. They didn’t get to meet the authors or members of Congress and share their perspectives.” As March 3 commemorates International Sex Workers Rights Day, sex workers are making their presence known on the 2020 national landscape.

March 2, 2020, 11:54 am

By Bella Robinson and prabhdeep singh kehal

“We passed these laws without even considering [consensual sex workers’] voices,” said United States Representative Ro Khanna. “They didn’t get to testify in Congress. They didn’t get to meet the authors or members of Congress and share their perspectives.”

As March 3 commemorates International Sex Workers Rights Day, sex workers are making their presence known on the 2020 national landscape. While national, progressive presidential platforms signal openness to the decriminalization of the sex trade industry, United States Representatives Ro Khanna and Barbara Lee and Senators Elizabeth Warren and Ron Wyden introduced the Safe Sex Workers Study Act in December 2019. The Act directs the United States Department of Health and Human Services to conduct the “first nationwide study on the health and safety of sex workers.” While increased research on how local, state, and federal legal enforcement harms sex workers’ livelihoods is welcomed, the Act makes no guarantee of sex workers or sex worker-led organizations being included as part of creating this study.

Instead, the Act solely aims to set the first stone of repealing SESTA/FOSTA, shepherding federal resources towards research supporting what sex workers have advocated for decades. Even Representative Khanna conceded: “We passed these laws without even considering [consensual sex workers’] voices. They didn’t get to testify in Congress. They didn’t get to meet the authors or members of Congress and share their perspectives.” Though acknowledging this as an issue in the passage of SESTA/FOSTA, the Act still includes no commitment on how sex workers would be included moving forward.

The Act comes in light of legislators responding to advocacy organizations’ pushback against the 2018 passage of SESTA/FOSTA. Though SESTA/FOSTA had been marketed as a social good, enabling increased law enforcement over sex trafficking platforms, the bills themselves did not distinguish between consensual sex work and trafficking. As a result, SESTA/FOSTA created additional hurdles to access health and safety resources for sex workers and further brought workers under the persecution of anti-trafficking laws. For example, eighteen and nineteen-year-olds are increasingly being charged with trafficking, including those who were victims of sex trafficking themselves.

As social justice organizations, such as Amnesty International, increasingly support global efforts towards decriminalization of the sex industry – at the same time a majority of Americans support decriminalization – where are the guarantees to sex workers for being at any decision making tables for the study? How is the expertise of sex workers, as workers, being included in efforts to craft future legislation? Importantly, how would the federal government reach out to sex workers to survey them, while legal defenses, such as “but your honor, she’s a whore”, are permissible in court?

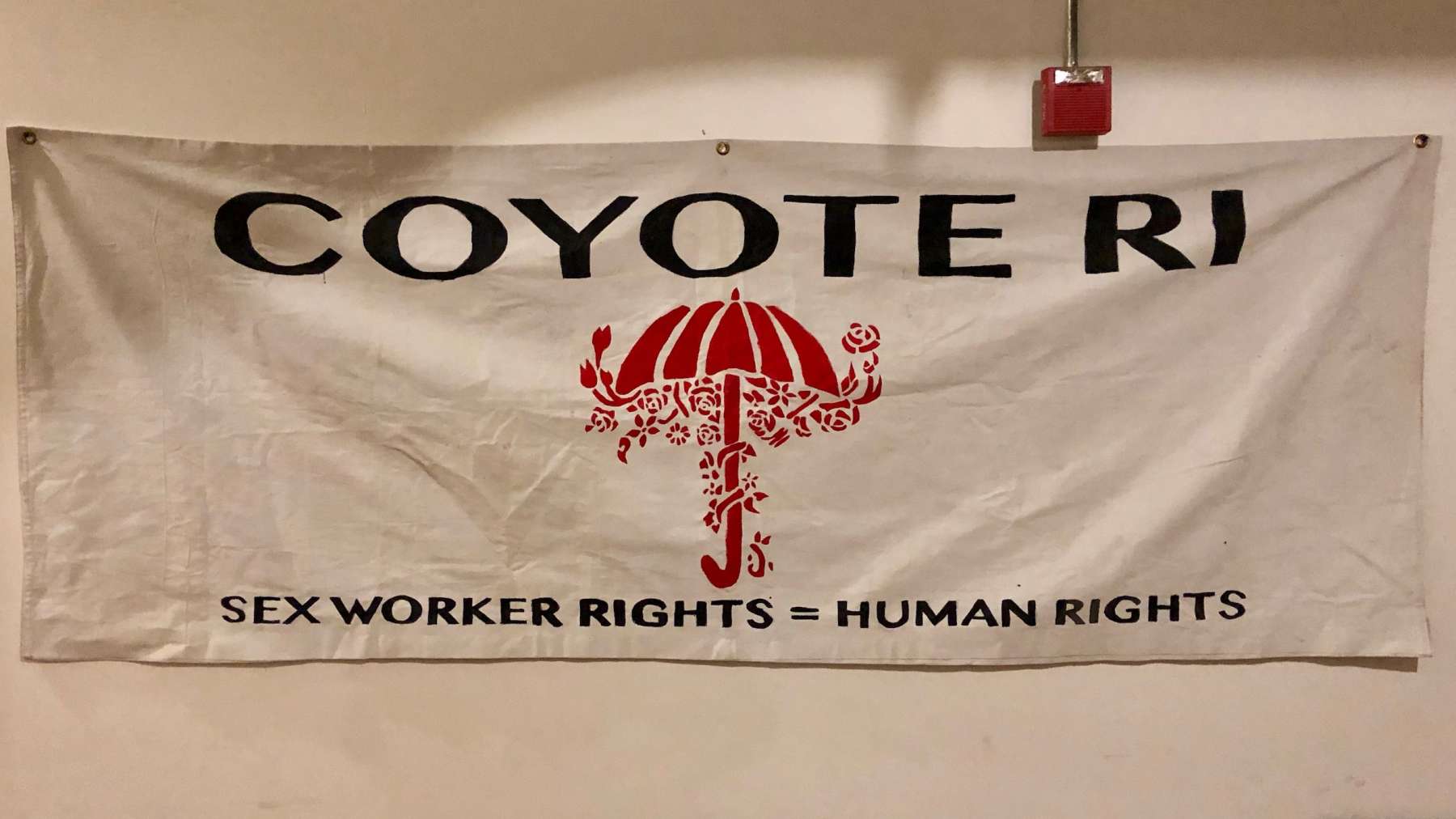

Despite an emerging political and cultural shift, recognizing the harm from existing criminalization efforts, sex workers, sex worker-led organizations, and scholars have been researching the effects of state and federal law on sex workers’ livelihoods, continuing the research that the Act aims to initiate. Coyote RI, a grassroots organization that uplifts sex workers rights as worker rights, conducted three separate surveys from 2014 until 2018 through support from the American Sociological Association and partnerships with Brown University’s Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice (CSSJ).

Under recriminalization of sex work in Rhode Island, Coyote’s study of 62 sex workers from 2014-2016 echoed worries from Tara Burns’ 2013 study on 40 Alaskan sex workers: workers were primarily concerned with violence or coercion from police and not being able to access equal protection under the law. In 2017, Coyote, along with other sex-worker led organizations, ran a comprehensive, national survey by using Backpage to reach 1,494 United States sex workers. Not only was the average age of entry among workers 22, but 78 percent of the sample worked in and outside the sex industry. For workers, the rise in policy on trafficking and the conflation of consensual sex work with trafficking led to anti-trafficking laws being expansively used to police and surveil workers.

As FOSTA shuttered the internet and dozens of sex worker platforms were removed in 2018, Coyote ran an impact study on 262 U.S. sex workers within two weeks of SESTA/FOSTA’s passage, finding a 28 percent drop in client screening practices, while 60 percent of sex workers took on less safe clients to make ends meet and 65 percent of workers said someone had tried to threaten, exploit, or get freebies from them. Collectively, the research highlighted how increased civilian vigilantism, alongside police surveillance and violence of already marginalized communities, such as migrant workers, resulted in carceral and prosecutorial – as opposed to social welfare – interventions.

Not only has policing and surveilling of consensual sex workers increased under FOSTA/SESTA, but using carceral solutions as social policy heightens the health impacts of criminalizing sex work. When indoor sex work in Rhode Island was temporarily decriminalized in 2003 – before Rhode Island legislators recriminalized it in 2009 – economists Cunningham and Shah found that reported rape offenses fell by 30 percent and female gonorrhea incidence declined by 40 percent under decriminalization. Similarly, in their 2020 framework for HIV prevention and action, medical researchers noted that decriminalization would likely reduce HIV incidence among sex workers by 33–46 percent.

The health disparities for sex workers are particularly important, as Coyote found that medical providers were not informing workers about PREP or PEP, harming the quality of health care provided to workers. Further, 48 percent of workers reported being treated differently by medical providers when they became aware of their involvement in the sex industry, increasing stigma towards workers. While more research needs to be conducted, we question legislators’ claims that the research would be more legitimate for policymaking, especially when their own research was not used in debating SESTA/FOSTA. Meanwhile, sex workers are already identifying proscriptive solutions towards decriminalization efforts. Federal legislators should include sex worker-led organizations as part of drafting policies that promote the health and safety of sex workers and that reduce violence, trafficking and exploitation. As states like Vermont (H568 and H569) and New York (S6419) introduce different type of decriminalization bills, other states and federal agencies should commit to having sex workers included in policy decisions. Otherwise, no research body would be legitimate without workers’ guaranteed input in the process.