Is turning waste plastic into fuel the answer to our waste management and energy woes?

Essentially, “you just took a fossil fuel, gave it a brief lifespan as a plastic, turned it back into a fossil fuel and burned it. That’s not renewable energy.” The first meeting of the “Special Legislative Commission to Study the Merits and Feasibility of a Pyrolysis or Gasification Facility in the State of Rhode Island” took place at the Rhode

March 13, 2020, 12:18 pm

By Steve Ahlquist

Essentially, “you just took a fossil fuel, gave it a brief lifespan as a plastic, turned it back into a fossil fuel and burned it. That’s not renewable energy.”

The first meeting of the “Special Legislative Commission to Study the Merits and Feasibility of a Pyrolysis or Gasification Facility in the State of Rhode Island” took place at the Rhode Island State House on Wednesday. The commission was established by the Rhode Island Senate towards the end of the 2019 legislative session after legislation to include pyrolysis or gasification as a green energy source failed to pass.

Though the stated purpose of the newly established commission is to “study the merits and feasibility of developing a pyrolysis or gasification facility in the state,” the enabling legislation gives a hint as to the bias of the commission, referring to pyrolysis as “an effective way to convert biomass, especially waste, agricultural waste and such, into useful fuels and products” and stating that “gasification plants produce significantly lower quantities of air pollutants.” After the first meeting of the commission ended, both of these assertions were in doubt.

“Solid waste management is an issue all over the world,” said commission chair Senator Frank Lombardo (Democrat, District 25, Johnston) near the opening of the commission hearing. “Alternative ways of disposing of waste or trash must be explored and gasification is one of those methods being considered.”

The commission includes seven members, including Senator Lombardo. Present for the inaugural meeting were:

- Paul Gonsalves, from the Rhode Island Department of Administration;

- Terry Gray from the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management;

- Chris Kearns from the Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources;

- Joseph Reposa, Executive Director of the Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation;

- John Riendeau, from the Department of Commerce; and

- Senator Susan Sosnowski (Democrat, District 37, Block Island, South Kingstown).

The first meeting was not open to public comment, but the third and final meeting will be. The second meeting of the commission will be scheduled for April.

Presenting at the first meeting was Craig Cookson, Senior Director Recycling and Recovery at the American Chemistry Council and Kevin Budris, a lawyer from Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) Rhode Island who heads up the Zero Waste Project.

Cookson’s presentation painted a very rosy picture of pyrolysis and gasification, Budris called into question or debunked nearly all of Cookson’s arguments.

Cookson argued that waste plastic, which is overwhelming or landfills, can best be dealt with by using pyrolysis to convert these plastics into liquid fuels, which can then be burned to power motor vehicles or satisfy other energy needs. Budris disagreed, saying that, “the best way to move away from waste plastics isn’t to find new, creative things to do with them once they become waste, it’s to just move away fro them.”

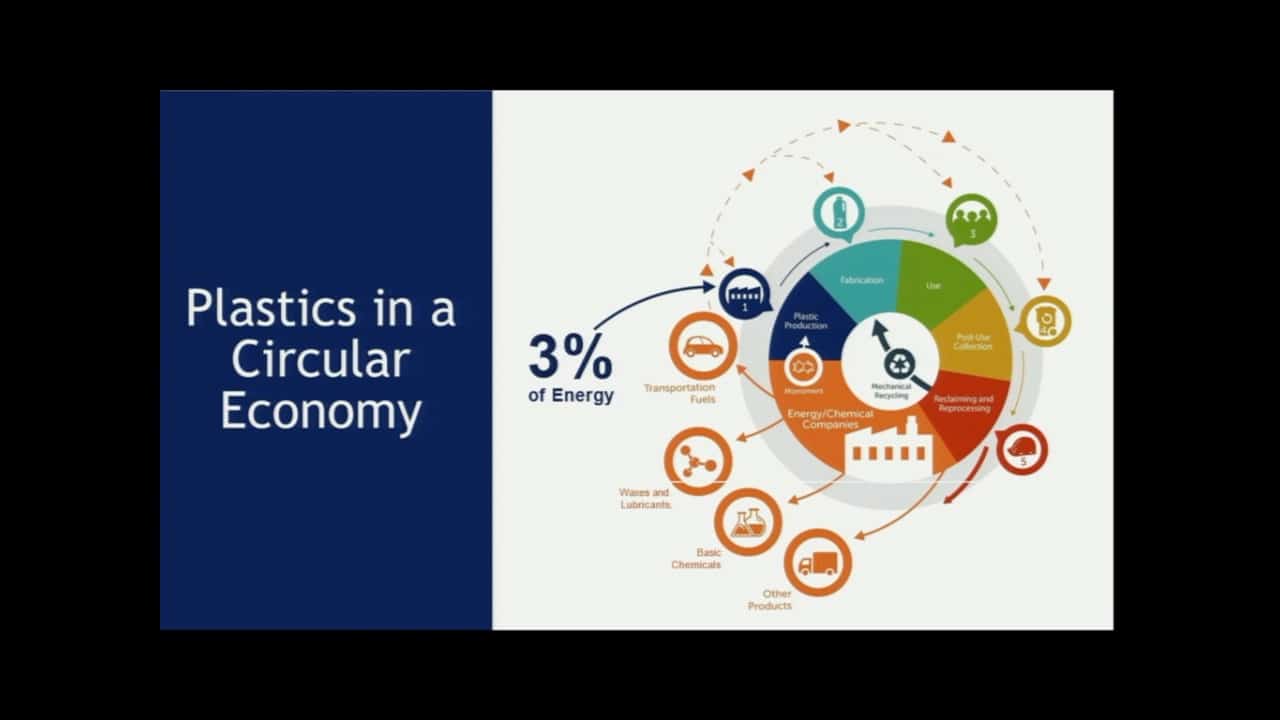

“Right now we take mainly natural gas in this country, turn it into plastics,” said Cookson. “We use and reuse them, and we collect them after use.” Cookson produced a slide entitled “Plastics in a Circular Economy” to show the process.

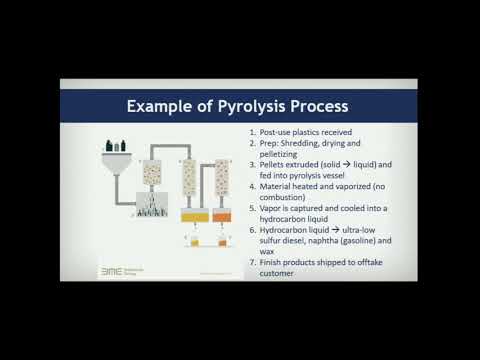

What pyrolysis and gasification do, said Cookson, is use the waste plastics to produce liquid fuels, chemical feedstocks, specialty chemicals and virgin-like plastics, among other uses.

Budris took issue with Cookson’s assertion that plastics are part of a “circular economy.”

“What we’re talking about here is producing fuels from plastics through gasification,” said Budris, countering Cookson. “Producing fuels from plastic is not a circular economy. That’s linear. You have plastic that moves through its life, it’s turned into fuel, and that fuel is burned. That is a one way street.

“Plastics,” continued Budris, “are not an alternative to fossil fuels. Plastics are fossil fuels. About 99 percent of the plastics that are produced in this country are derived from fossil fuels. Fossil fuels are the building blocks of the carbon based polymers that plastics consist of.”

During his presentation, Cookson frequently said that the process of pyrolysis requires “no combustion,” that is, the process does not burn plastic, it turns plastics into liquid fuels. “The only combustion is a little bit of natural gas to help heat the vessel up… which is no different than the boiler in your basement producing your heat for the winter.”

Though this is technically all true, Budris pointed out that it is true because advocates of pyrolysis, like Cookson and the American Chemistry Council he represents, divide the full process into two. “Gasification and pyrolysis are not mass burn incineration, but they are comparable to mass burn incineration, split into two parts. Mr Cookson repeatedly emphasized there’s no combustion – but what happens to the fuel that’s produced from the gasification of plastics? That fuel is combusted.”

Essentially, said Budris, “you just took a fossil fuel, gave it a brief lifespan as a plastic, turned it back into a fossil fuel and burned it. That’s not renewable energy.”

When you look at the full process, said Budris, you end up with a lot of the same emissions you get through incineration.

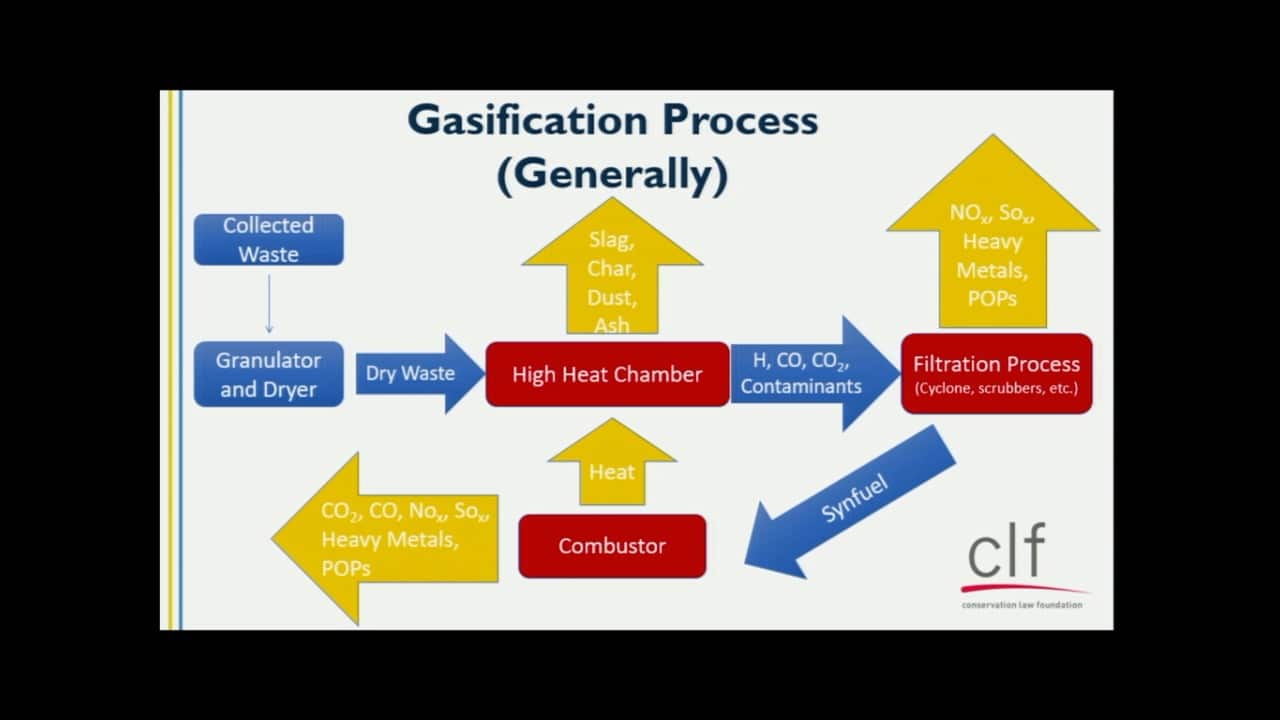

Budris presented a very different slide explaining the gasification process. Gasification not only generates the wonderful products Cookson mentioned, it also generates waste products in the form of slag, char, dust and ash. This is because none of these waste product inputs are pure. They all contain some level of impurities that will be left behind. These solid waste leftovers are filled with toxins.

The same thing happens after the liquid fuel is filtered. Again, impurities need to be removed, resulting in green house gases like NOx, and dangerous chemicals like SOx, heavy metals like lead and mercury, persistent organic pollutants like dioxins, and more. These waste products have to be dealt with, and there are no facilities near Rhode Island to do so. Finally, the synthetic fuel that is the point of gasification is then burned, to heat the gasification process itself or shipped off for use in motor vehicles. The burning of this fuel produces all the effects one has come to expect from burning fossil fuels, in the form of CO2, CO, NOx, SOx, heavy metals and POPs.

The emissions profile from this synthetic fuel are actually worse than the emissions from fracked gas, diesel or gasoline.

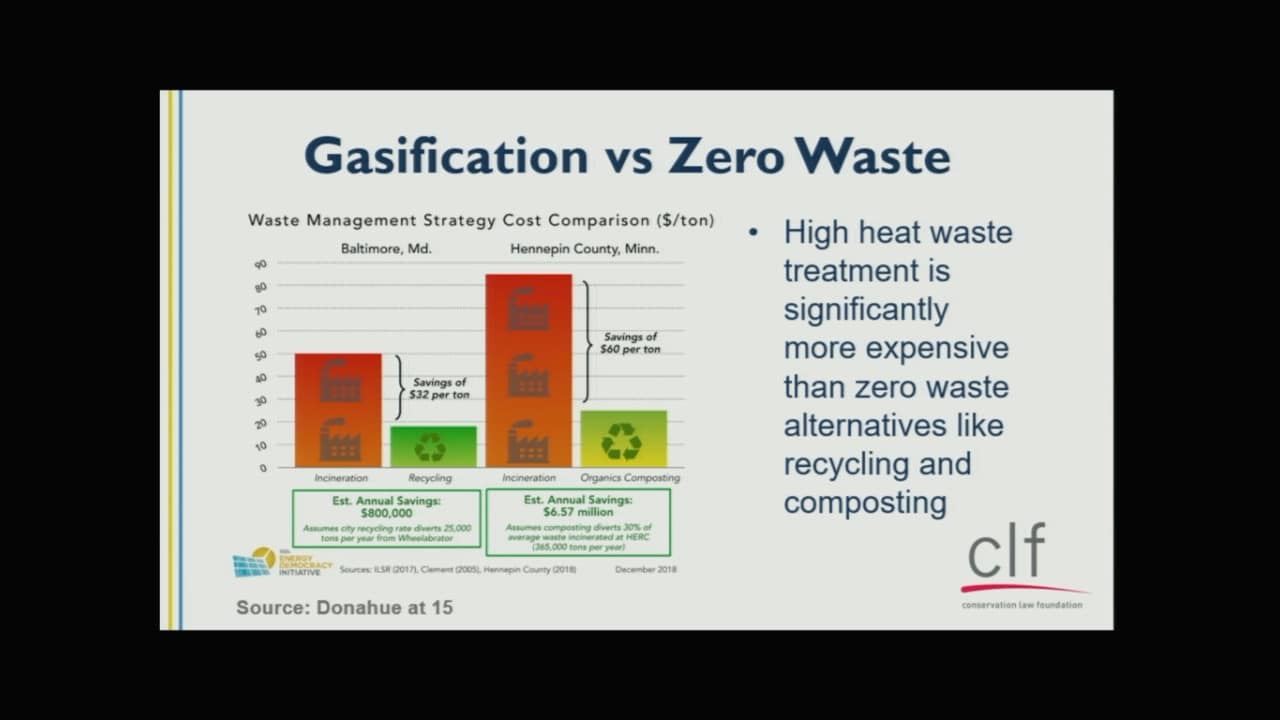

Budris made the case for source reductions of plastic, as well as recycling and composting of organic matter. These technologies can deal with plastic waste better by preventing plastics from entering the cycle to begin with. Through aggressive application of these ideas, we can ease the demands on our landfill. “These processes conserve more energy than you can ever hope to generate out of a gasifier,” said Budris.

Gasification and pyrolysis consume as much as 87 times more energy than can be generated by burning the synthetic fuel they produce. Gasification chambers run anywhere from 700 to 2800 degrees Fahrenheit. That requires more than the “small amount of natural gas” Cookson suggested, said Budris, because “the laws of thermodynamics are inviolable – If you need to create so much heat to create fuel, you cannot get more energy out of that fuel than you used to create the fuel in the first place.”

Gasification is also quite expensive, notes Budris. A gasifier with a 15 MW output is going to cost as much as $172.5m, more than twice the capital costs of wind and solar. These costs translate into high tipping fees, that is, these facilities will have to charge money to take in the waste plastics they are collecting. If built, Rhode Islanders will be paying this plant to take our plastics.

Budris hammered home the point that gasification and pyrolysis are more expensive options that zero waste alternatives like recycling and composting.

Composting generates between four and 15 times as many jobs as gasification or pyrolysis. Recycling generates between 12 and 20 times more jobs.

Budris ended his presentation with what he called a “long history of failure” for gasification and pyrolysis plants. Most of the success stories brought up by Cookson in his presentation are relatively new. In Scotland, Canada, Germany and Australia these plants exceeded emissions standards and closed, resulting in bankruptcy billions of dollars in wasted money.

Below is all the video from the meeting, starting with the presentation of Craig Cookson, representing the American Chemistry Council:

Kevin Budris from CLF:

Cookson takes questions from commission members:

Budris takes questions from Commission members:

The opening of the first meeting: