Out of Sight, Out of Mind

Rhode Island’s High Security Correctional Facility is currently home to 78 incarcerated individuals. Colloquially known as ‘High Side,’ the facility has recently come under scrutiny for its use of long-term solitary confinement amidst the global movement to end this practice in prisons and jails.

March 22, 2021, 10:00 am

By and

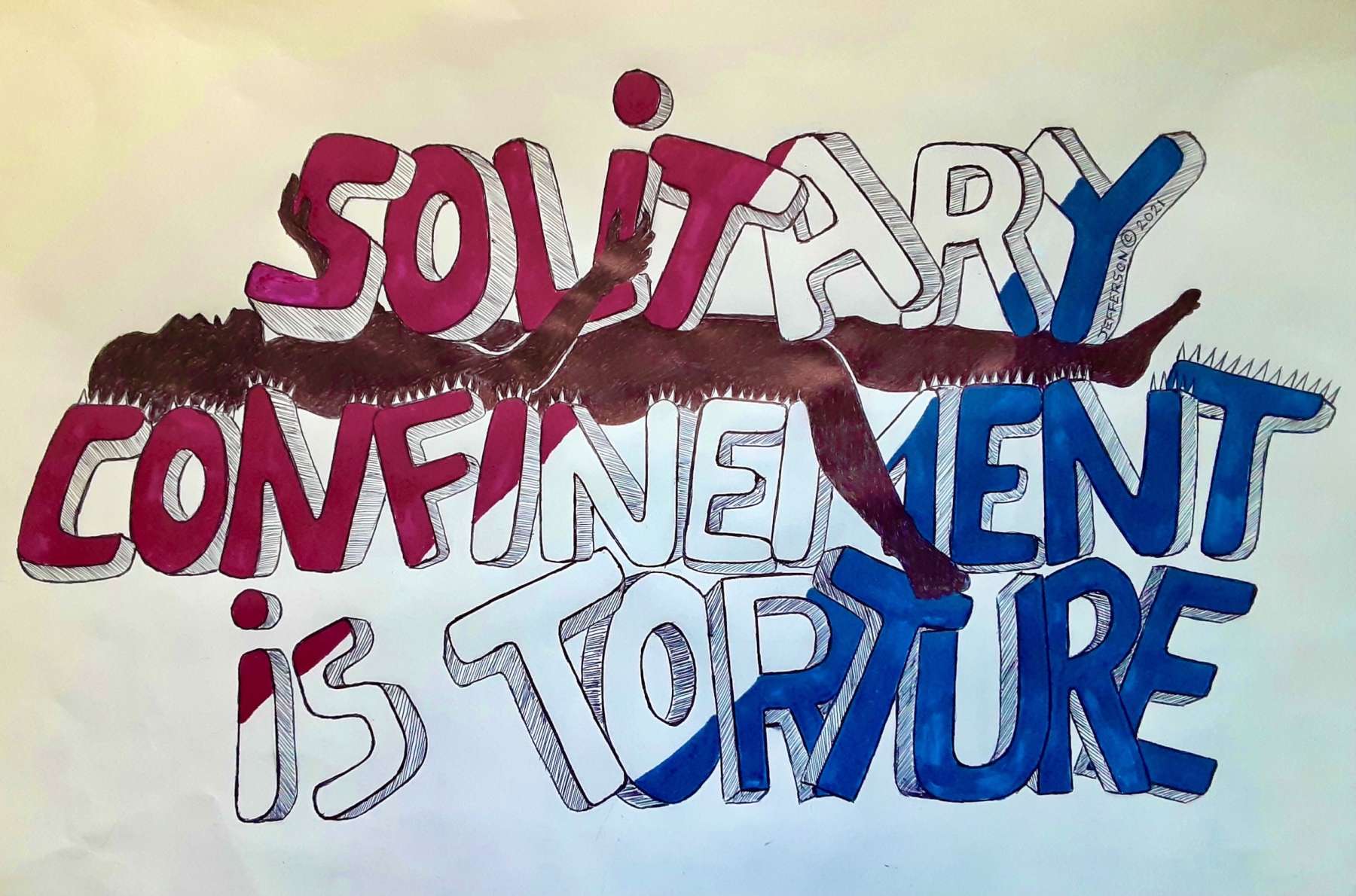

Please note that names with an asterisk (*) are pseudonyms, used to protect interviewees. The art at the top of this piece is from Leonard Jefferson.

Shrouded by trees and dying bushes, kept out of sight from passersby, Rhode Island’s High Security Correctional Facility is currently home to 78 incarcerated individuals. Colloquially known as ‘High Side,’ the facility has recently come under scrutiny for its use of long-term solitary confinement amidst the global movement to end this practice in prisons and jails.

The United Nations defines solitary confinement as individuals being “held in isolation from others, except guards, for at least 22 hours a day.” Publicly, the Rhode Island Department of Corrections (RIDOC) has maintained that the Adult Correctional Institutions (ACI) does not use solitary confinement. Instead, when the RIDOC confines people in their cell for 22 hours or more, it is referred to as “restrictive housing.” The two primary forms of restrictive housing are disciplinary and administrative confinement.

Disciplinary confinement occurs in each of the facilities of the ACI and can be used as a punishment for a wide range of non-violent and violent infractions. Administrative confinement is a security classification, used when RIDOC staff believes an individual is “dangerous to him/herself or others” or shows a “chronic inability to adjust to the general population,” amongst other reasons. All individuals classified to administrative confinement are housed in High Side. According to publicly available policy, people classified to administrative confinement are supposed to have their security status reassessed every 90 days, but the actual amount of time they can remain there is indefinite. In both forms of restrictive housing, incarcerated people are confined to their cells on a “23 and 1” schedule—23 hours in their cell and 1 hour of recreation time. This schedule also occurs for other residents of High Side who are not in administrative confinement, such as those in protective custody. These conditions, despite RIDOC’s persistent declarations, constitute solitary confinement.

Losing oneself to High Side

For former High Side residents with various classifications, the monotony of their days was compounded by isolation and dehumanization. Individuals were woken up at 7-7:30 am each day and were allowed one hour of “recreation time”; this hour was spent handcuffed in an outdoor cage. They were then taken to shower for five minutes, and then were returned to their 8×10 foot cell where they spent the remainder of the day. On weekends and holidays, they did not receive out of cell time at all. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner were all served through slots on the cell door.

Tyrone Scholl, a 58 year old man who spent approximately four years in High Side across different periods of incarceration, told Uprise, “The food you get has no taste, it’s all plain. They gave little portions, just enough for you to survive. For lunch we get a little bit of tuna fish on a slice of bread or sometimes a grilled cheese and chips. At dinner, you get a little bowl of rice and meat. Sometimes the meat you get is spoiled, it don’t taste right. You’re never full after you’re done eating and the food is definitely not healthy.”

While in solitary confinement, individuals have few opportunities to make choices about their bodies, but once a week, High Side residents are allowed to order food from the commissary. Dr. Rahul Vanjani, a Rhode Island physician who formerly practiced medicine at San Quentin State Prison in California, told Uprise that those in solitary particularly look forward to commissary permissions, though there are hardly any healthy options. He said, “People always described that to me as being associated with stress-eating because there’s nothing else to look forward to in solitary, you can’t even look forward to spending time with friends in the yard or calling home. But the one thing you can look forward to is the consumption of junk food. That clearly has a negative impact on people’s health.”

Poor nutrition is but one of many health-related issues those in High Side suffer through. Former residents also explained how being isolated to their small cells and receiving inadequate mental health services chipped away at their sense of self.

“Living in High Side was hell,” said Roy*. “Everyday there my life was like an emotional roller coaster. I would be struggling from depression, and they would know I was struggling, but they wouldn’t do anything to help me. They were just waiting for me to commit suicide.”

Roy, a 45 year old Black man, spent four years incarcerated in High Side and was released in 2020. Having struggled with his mental health throughout his life, being confined for 23 hours a day exacerbated his symptoms significantly. At one point, his depression became so severe that he would not leave his cell during his one hour of recreation time. In fact, there were many days where Roy felt like his only option was to attempt suicide—and he was not alone.

“A lot of guys that are in there are struggling with mental health issues and if you don’t have anything that gives you hope and you commit suicide, it’s just blamed on you,” he said. “They don’t care. I know guys who committed suicide because they were just confined for hours and hours.”

There is a significant amount of scientific literature that confirms the devastating impacts of solitary confinement on the mental health of incarcerated people. Dr. Craig Kaufmann, a psychiatrist who works with individuals experiencing homelessness, started his early career in psychiatry at the ACI’s Medium I and Women’s facilities. He quickly identified a common thread between all of his patients in prison: a vast trauma history which started in childhood. From unstable home environments to structural oppression, his patients often spoke about significant traumatic events they never received care for.

“And what I hear when I speak to folks is that there is a re-traumatization process happening in prison,” Kaufmann told Uprise. “The experience of being deprived of resources and social contact exacerbates pre-existing PTSD, psychotic symptoms, hallucinations and delusional thinking. And in terms of solitary, some of the first literature on suicide proposed that suicide is the end result of extreme social isolation. I always think of that when I think of these extremely isolating experiences, like being incarcerated and being remanded to solitary.”

Two forms of “care”: indifference and violence

Lack of mental health care is a common experience for incarcerated populations, both pre-confinement and during. Tyrone told Uprise that he did not receive any care and instead tried to keep himself sane while in High Side. “Don’t get me wrong, what they do will drive you crazy. You put in a slip that you want to see a doctor but it will take 2 or 3 months before you get to see them. When you do see a doctor and you let them know something is going on in your head, they will just put you on meds. For physical health, you just get Tylenol. That’s their answer for everything.”

Tyrone also felt that mental health staff had closer relationships with the COs than their patients, leading to punitive responses to mental health crises. Joseph Shepard, who spent three and a half years in High Side, described correctional staff’s apathy towards individuals in crisis at a rally organized by Decarcerate NOW.

“When we have a mental health breakdown in the cell… there’s a slot in the door, they open that slot, they spray a riot sized mace can until you almost pass out,” Shepard said at the rally. “If you continue to have a mental health breakdown, they’re going to spray another one. And then when you fall, they come in the cell, five, six, seven people, they cuff you up… they strip you butt naked and drag you to the shower…Remember, we’re all dehumanized.”

Most former residents agree that High Side is functionally unable to provide the depth of mental health support necessary for its population. Interviewees told Uprise that in their experiences, one social worker would speak to some incarcerated individuals for only a few minutes through the slot on their cell doors, within earshot of COs. With hope for more comprehensive sessions, individuals were taken to the social worker’s office once a month.

Roy elaborated, “But, if the guards don’t trust you with what you’re going to say, they leave the door open so they can listen to what you’re talking about. It’s really no type of mental health care, the social worker is not equipped to actually help anyone. High Side is set up to seem like it cares about you and wants to rehabilitate you but they’re not doing any of that.”

For some, mental health care was never even presented as an option. Dennis*, a 33 year old Black man, was 16 when he was sent to High Side for two years. Originally held in the Rhode Island Training School, the state’s juvenile detention facility, he was moved to the Intake Service Center after the courts decided to try him as an adult. He was then placed in a single cell in High Side’s protective custody block while he awaited his sentence. There, he was alone for 23 hours a day.

“That was my first time really incarcerated and all of that was new to me,” Dennis told Uprise. “They didn’t tell me what to expect or anything. I seen guys go crazy in there. But you know, they never mentioned there was any mental health care, they wouldn’t even come by our block and ask you ‘is anything wrong with you?’ There was none of that.”

On the practitioner side, there are additional challenges to meeting a standard level of care that one would otherwise be able to achieve outside of High Side’s walls. Dr. Kaufmann said that his working environment in Medium I and Women’s was very different to High Side, given that High Side holds more people with severe presentations of mental illness.

“Part of treatment [for them] has to involve being in an environment that is therapeutic and prison is not that. Folks who are significantly ill and not incarcerated would probably be receiving a higher level of services besides seeing someone for medication. It’s hard to imagine how that level of care can be provided in a prison setting. And providing care through a cell door, to me, that is entirely not what psychiatric care should be. Day after day of just being asked if you’re doing okay through a cell door is not the standard of care.”

In Rhode Island, there is currently a federal class action lawsuit against the Department of Corrections on behalf of incarcerated individuals with mental illness who have spent time or are at risk of being placed in solitary. The lawsuit claims that men and women with existing mental health symptoms are subjected to prolonged solitary confinement and that RIDOC ignores written requests to be removed from those conditions, even after self-injurious behaviors.

A tool for safety or abuse?

“The way we look at solitary confinement—it’s a tool,” said Richard Ferruccio, former president of the Rhode Island Brotherhood of Correctional Officers, to the Wall Street Journal. As he later expressed to the College Hill Independent, Ferruccio views solitary confinement as a tool to maintain safety and security within the ACI. This is a common misconception often leveraged by corrections departments who oppose reforms to the practice.

Emerging research has shown that solitary confinement has no effect on prison violence. A study on the supermax facilities in Arizona, Illinois and Minnesota found no decrease in interpersonal violence between incarcerated individuals. Meanwhile, states at the forefront of limiting the use of solitary have found a significant reduction in violence and misconduct; in 2007, when Mississippi moved three quarters of their supermax residents to the general population, they saw a 70% reduction in overall violence between incarcerated people as well as between those incarcerated and staff. Furthermore, corrections directors in Colorado and North Dakota have found no increase in violence against correctional staff after reducing the use of solitary confinement.

Ferruccio is correct to be concerned about violence within the ACI; withholding proper mental health treatment and severely restricting human interaction and movement are all forms of violence that former and current residents of High Side report experiencing. Additionally, interviewees described incidents of physical abuse at the hands of COs.

Roy recounted disturbing violence, saying that COs would be aware of interpersonal issues or aggression between two residents and purposefully stage fights between them.

“A guard would bring two guys to the cages, take one of the guys’ cuffs off first and would let them assault the other inmate. The guards would just sit there and watch for a while. They also have computers where they will re-watch the fights on their monitors.”

Dennis added that High Side had cameras lining the building, which COs would use to listen in on arguments between residents who sometimes yelled at each other from their cell doors. “When they would hear guys arguing they would then put those two people in the cage together” he confirmed to Uprise. “They call it the dog pound or the dog kennel because of the fenced cages and the fights.”

After spending four years in High Side, Mike*, a 64 year old man, re-classified back to Maximum and spoke with other people about their experiences with guards in administrative confinement. Though he mentioned that there were some officers who looked out for residents, “there were also just bad dudes.” He reflected on one specific story about a friend who was beat up while in High Side by officer Gualter Botas.

“An officer, his name is Botas, beat up a friend of mine while he was still in handcuffs. It was reported to the ACI but I know he never got in trouble because he later became captain in Minimum. While he was in Minimum, he caught a kid hiding cigarettes in his rectum and he made the kid eat them. I want to know how he became captain even after beating my friend up.”

Botas was eventually sentenced to prison in 2013, when he was found guilty of seven counts of assaulting and abusing incarcerated individuals throughout the ACI.

Lasting impacts of trauma

“I’ve been in every ACI building and High Side is its own world,” Dennis emphasized. “If the guards don’t like you, you’re in a world of trouble. They control everything. If they don’t let you on the phone or give you your mail, you disappear from the world. Nobody’s coming to check on you. If you’re stuck you’re really just stuck. High Side disappears you.”

In addition to the traumatic experiences incarcerated individuals have had while residing in High Side, the impacts of solitary confinement follow people long after they have been released.

Roy has been struggling with his self-esteem, has unshakeable trust issues, and feels increasingly nervous when he is around people in public spaces. Because of this, he isolates, creating even more of a distance between himself and his family from whom he was separated from for years during incarceration. Mike is frightened by loud noises, citing his intolerance of sounds to the constant silence in High Side that was periodically interrupted with a slamming door or screaming. Tyrone has a looming sense of needing to protect himself in situations other people may deem relatively safe, like sitting on the bus or waiting in a building. He said that his back is always to the wall so that he can watch people passing by him.

Some of Dr. Kaufmann’s current clients who previously spent time in High Side have also spoken about the impact of hearing people in crisis in their neighboring cell and making futile attempts to get help. “It’s survivor’s guilt,” Dr. Kaufmann said. “They tried to yell out to get help but it wasn’t viewed as an emergency. It’s another form of powerlessness they felt and that causes lasting trauma.”

At the Decarcerate NOW rally Joseph explained, “We call these facilities rehabilitation centers, we call them correctional facilities. We are not being corrected in these facilities. We are being dehumanized, we are being tortured.”

Those who are eventually released from High Side do not leave unscathed. “Every day is a struggle for me, every day it feels like I’m by myself,” Roy shared, his voice shaking. “The years that I was locked up, I feel like I have completely lost myself. Now I’m out and I’m living, but I’m not really living.”

A special thank you to our interviewees for sharing their experiences and to Leonard Jefferson for creating the header artwork.