RI Housing Crisis Deepens as National Report Shows Young Buyers Shut Out of Market

The typical first-time homebuyer is now 40 years old as a flood of all-cash offers from wealthy investors locks a generation out of the market. This isn’t just a housing crisis; it’s the creation of a permanent rental class. Read how our economy is being redesigned to ensure you own nothing.

November 11, 2025, 9:31 am

By Uprise RI Staff

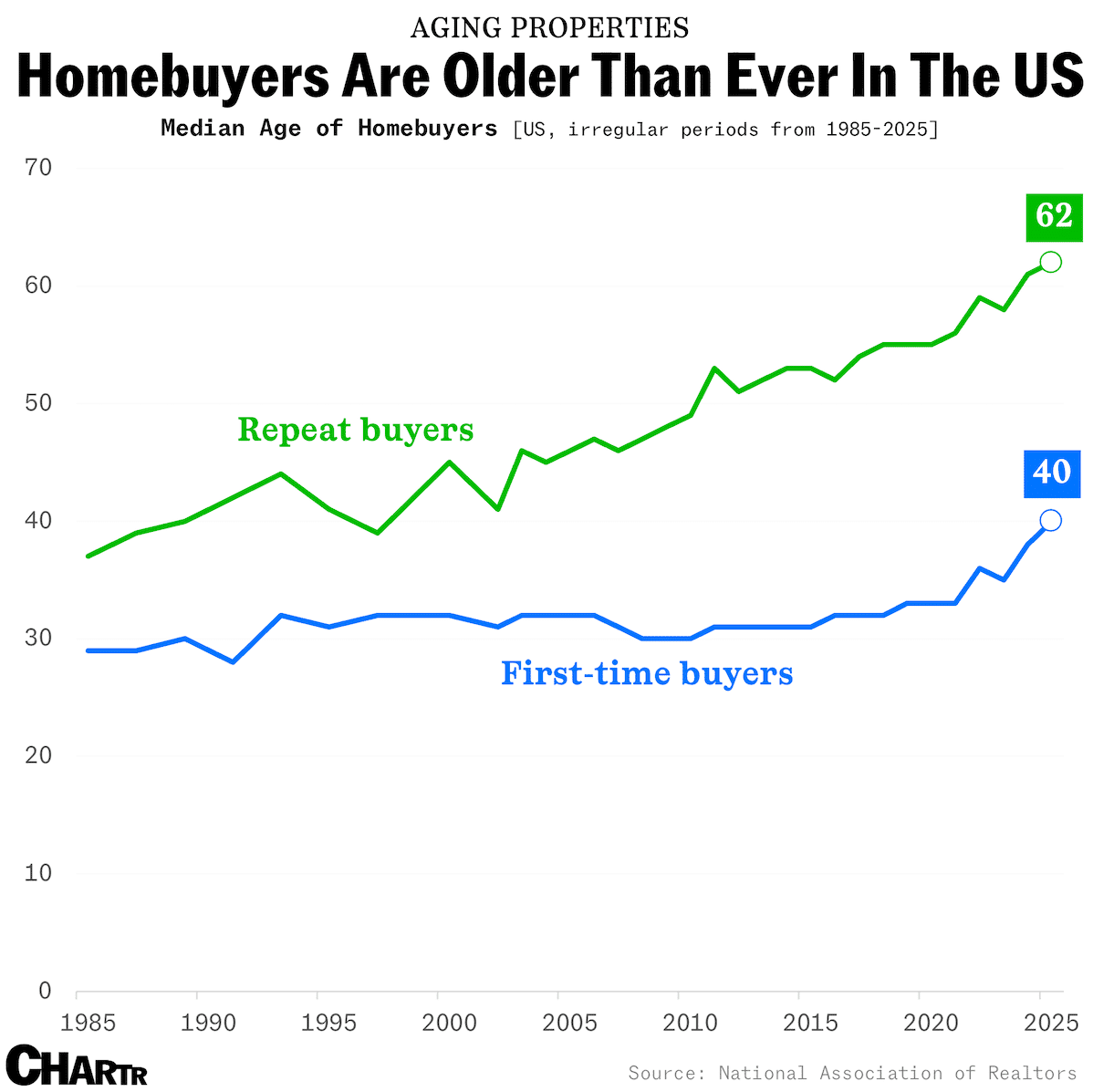

The so-called American Dream is being pushed further out of reach, and for a growing number of Americans, it may never arrive at all. A new report from the National Association of Realtors paints a grim picture of a housing market fundamentally broken for ordinary people, revealing that the typical age of a first-time homebuyer has climbed to an all-time high of 40 years old.

The annual survey, which covers home sales from July 2024 to June 2025, found that the share of first-time buyers in the market has collapsed to a record low of just 21%. For context, this share has been cut in half since 2007.

“The historically low share of first-time buyers underscores the real-world consequences of a housing market starved for affordable inventory,” said Jessica Lautz, NAR’s deputy chief economist. “The implications for the housing market are staggering. Today’s first-time buyers are building less housing wealth and will likely have fewer moves over a lifetime as a result.”

The report highlights a widening chasm in the housing market, creating two parallel realities. “Unfolding in the housing market is a tale of two cities,” Lautz explained. “We’re seeing buyers with significant housing equity making larger down payments and all-cash offers, while first-time buyers continue to struggle to enter the market.”

While first-time buyers scraped together a median down payment of 10% – sourcing funds from personal savings, 401(k) raids, and loans from family – repeat buyers, with a median age of 62, were able to put down 23%. A stunning 30% of these repeat buyers purchased their homes with all-cash offers, a tactic that often prices-out younger buyers who rely on traditional mortgages.

This national crisis is felt acutely here in Rhode Island. According to a recent factbook from HousingWorks RI, 2025 is the first year the state’s median renter, earning an income of $48,434, cannot afford an average two-bedroom apartment anywhere in the state. The income needed is over $60,000. Last year already marked a bleak milestone: no single community in Rhode Island was considered affordable for a household earning less than $100,000. “Rhode Islanders continued to face a challenging housing market,” the report states simply.

This affordability blockade is not a bug in the system; it is increasingly the feature. By locking millions out of ownership, the housing crisis is accelerating a disturbing trend in late-stage capitalism: the “rental model.” In this new economy, the goal is not for you to own assets, but to perpetually pay rent on everything – from your software and your music to the very roof over your head. This creates a permanent class of tenants who cannot build the intergenerational wealth that homeownership has traditionally provided.

As Shannon McGahn, NAR’s chief advocacy officer, points out, the financial loss is quantifiable. “Delayed or denied homeownership until age 40 instead of 30 can mean losing roughly $150,000 in equity on a typical starter home,” she said.

In Rhode Island, state leaders have pushed for more construction as the primary solution, easing zoning and permitting rules. But Brenda Clement, executive director for HousingWorks RI, notes the limitations. “What you build, where you build, and how you build are all at the local level,” she said, pointing to towns like Johnston and Westerly that are actively fighting denser housing projects.

But even if municipalities get on board, a more fundamental problem remains. Merely building more homes does not guarantee they will go to the people who need them. Against a backdrop where deep-pocketed investors are snapping up an estimated 30% of homes for sale nationally, new inventory can easily be absorbed by corporate landlords and house-flippers, further constricting supply for regular families and driving up rents.

The problem isn’t just a lack of supply; it’s who is buying it. A more direct solution is needed to level the playing field. Instead of just focusing on construction, Rhode Island could consider policy that disincentivizes the commodification of housing itself. A progressively structured tax on non-owner-occupied properties, where the tax rate increases with each additional property owned, could be a powerful tool. Such a policy would have minimal impact on a small landlord who inherited a family two-family home, but it would make it far less profitable for a private equity firm to buy up dozens or hundreds of single-family homes to turn into rentals.

This would cool the investor frenzy and give first-time buyers a fighting chance. Without systemic changes that prioritize housing as a human right over a financial asset, the dream will continue to recede. As Clement of HousingWorks RI reminds us, the stakes are higher than just dollars and cents. “Nothing works right in your life if you don’t have a decent place to get up from every day and to go back to every night.”

Was this article of value?

We are an reader-supported publication with no paywalls or fees to read our content. We rely instead on generous donations from readers like you. Please help support us.