When one and one doesn’t equal two

“Two-thirds of the benefit from a tax exemption for retirement income would flow to the richest 20 percent of Rhode Islanders,” writes Andy Boardman, “and a bump in the estate tax threshold would help the heirs of about 300 large estates.” In politics, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is among the most worn and predictable of literary references. Allusions to Big

February 17, 2020, 7:25 am

By Andy Boardman

“Two-thirds of the benefit from a tax exemption for retirement income would flow to the richest 20 percent of Rhode Islanders,” writes Andy Boardman, “and a bump in the estate tax threshold would help the heirs of about 300 large estates.”

In politics, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is among the most worn and predictable of literary references. Allusions to Big Brother, Newspeak and war with Eastasia so saturate our political dialect that one almost cringes to draw the connection between the novel and some contemporary happening.

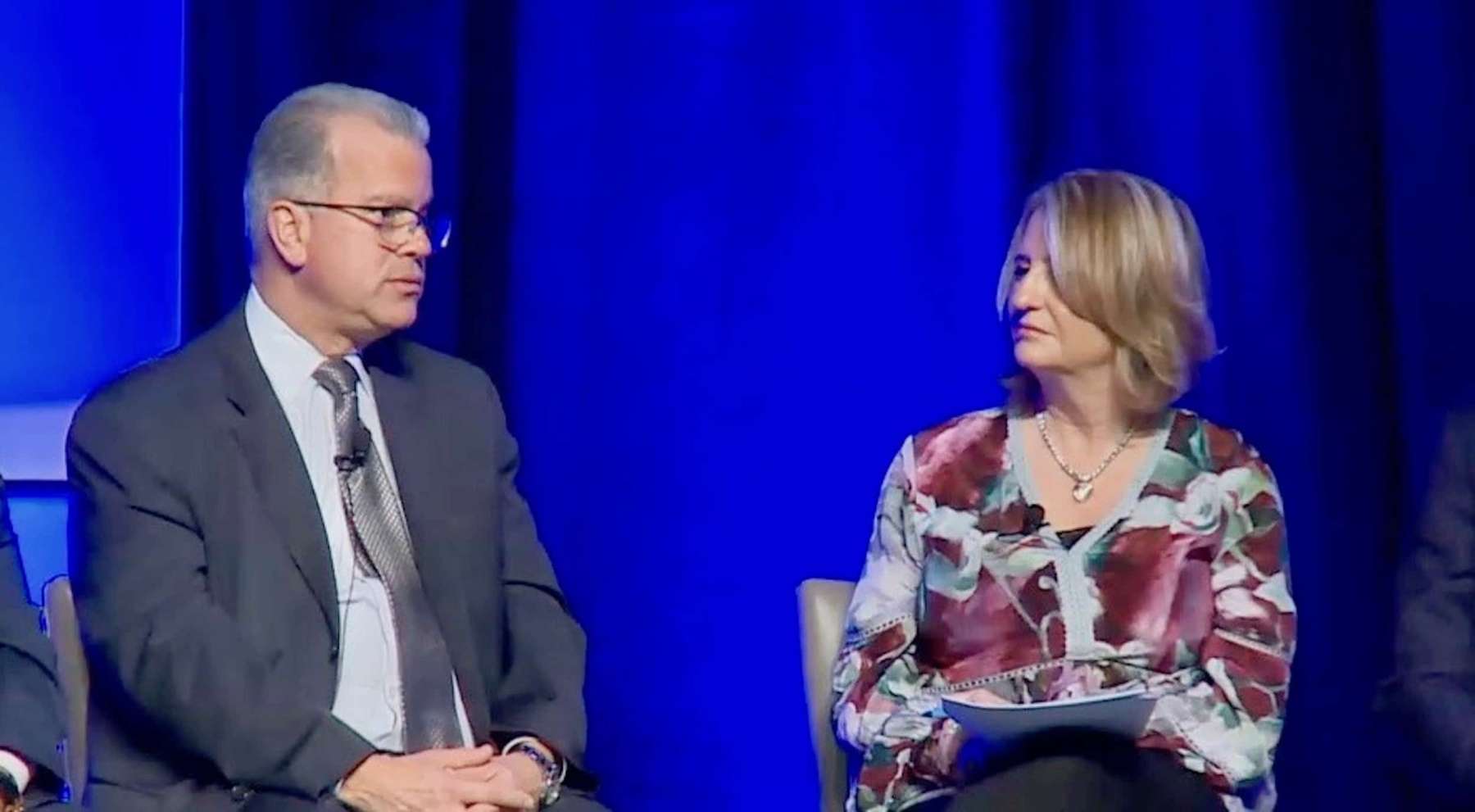

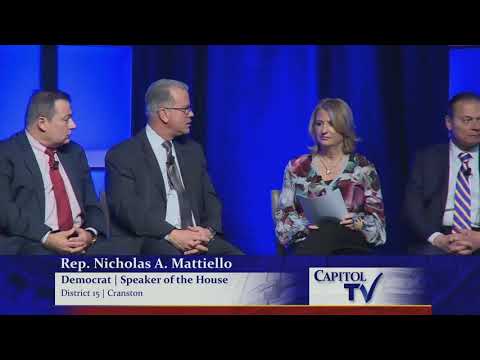

But listening to legislative leaders at last week’s Greater Providence Chamber of Commerce legislative luncheon, one can’t help but be reminded of The Party’s slogan, 2 + 2 = 5.

Take the following exchange between Chamber president Laurie White and House Speaker Nicholas Mattiello:

White: Is there anything [in the governor’s proposed budget] you foresee at the moment that you have a particularly dim view of?

Mattiello: No. What I will say is I like all of the ideas, the big picture. I like the ideas, but at the end of the day, one and one has to equal two. So that’s the perspective that it has to be viewed in. If we didn’t have to worry about how we were going to pay for it, they’re all great. I’m all in.

But that’s not the reality of our assignment. And the Finance Committee—and my appreciation really goes out to the chairman and each one of them, in both committees, the House and the Senate—because they’ve got a difficult task this year.

So they’re going to listen to the testimony, they’re going to assess the pros and cons of each initiative, and we’ll all come up with a balance that works. I could not tell you which ones I think are great, or which ones I think might fall off the table, until we go through that process.

When it comes to the governor’s agenda—pre-kindergarten, affordable housing, job training and so on—“one and one must equal two,” the speaker says. Expenditures and revenue need to add up, and each proposed program must be carefully considered against competing priorities.

But this math does not hold on all occasions. Later in the event, White asks Mattiello, House Minority Leader Blake Filippi, House Majority Leader Joseph Shekarchi, Senate President Dominick Ruggerio, Senate Majority Leader Michael McCaffrey and Senate Minority Leader Dennis Algiere about a pair of Chamber-backed tax proposals. As if a switch were flipped, equivocation gives way to enthusiasm:

White: Do you support a phase-out of the tax load on retirement income?

Filippi: 100 percent, yes.

Shekarchi: Yes.

Mattiello: Yes, we already started the process.

Ruggerio: Yes.

McCaffrey: Yes.

Algiere: Yes.

White: Good.

White: How about increasing the current threshold on estate taxes? … The threshold currently stands at $1.579 million. So, yes or no: Should we be working to increase that threshold to a higher number?

Filippi: Yes, definitely.

Shekarchi: Yes.

Mattiello: Yes, absolutely.

Ruggerio: Yes.

McCaffrey: Yes.

Algiere: Yes.

As we see, these proposals are so self-evidently good that they require no mention of tradeoffs or competing priorities. One and one need not equal two. What distinguishes this pair of ideas from others? Here’s a hint: Two-thirds of the benefit from a tax exemption for retirement income would flow to the richest 20 percent of Rhode Islanders, and a bump in the estate tax threshold would help the heirs of about 300 large estates.

Of course, one and one equals two whether acknowledged or not. The state is required by law to balance its budget, and tax cuts for the wealthy are rarely free lunches. If enacted, they will sooner or later force tough choices—choices lawmakers seem unprepared to make.

Rhode Island has been down this path before. Beginning in 2006, the General Assembly and Governor Donald Carcieri drastically reduced taxes for high-income Rhode Islanders with no pay-for plan—a textbook example of the selective budget math some legislators employ today. Tax revenue cratered, prompting painful program and staffing cuts that harmed the state’s response to the Great Recession. Rather than defend or criticize the reform, Mattiello asserted in 2015 that “realistically, there’s never been tax cuts for the rich.”

State leaders can stop themselves from repeating the same misjudgement. But first, they have to cut out the doublespeak and accept that one and one always equals two.