On the 400 year anniversary of the English arrival on the homelands of the Wampanoag

“Today, as Massasoit’s tribal community, the Pokanoket, we are land less. Mega-million dollar universities, corporations and land trusts privately own our sacred homelands and are not willing to part with them, and the funding to give our story a voice never seems a priority,” says historian and artist, Deborah Spears Moorehead. Events are planned for this year’s 400 year anniversary

February 27, 2020, 10:20 am

By Ezme Webb-Hines

“Today, as Massasoit’s tribal community, the Pokanoket, we are land less. Mega-million dollar universities, corporations and land trusts privately own our sacred homelands and are not willing to part with them, and the funding to give our story a voice never seems a priority,” says historian and artist, Deborah Spears Moorehead.

Events are planned for this year’s 400 year anniversary of the English arrival on the homelands of the Wampanoag, which invites reflecting on the ongoing consequences for our region, our selves and our planet.

In 1620 the sovereign nation of the Pokanoket Wampanoags was a politically organized area throughout Massachusetts and southern parts of Rhode Island, with thirty tribute tribes under Massasoit‘s Pokanoket leadership council.

Pokanoket meaning ‘cleared land near the bay’, and Wampanoag, the ‘People of the First Light or People of the East.’

After being moved on by Nausett Wampanoags from where they landed in 1620, the first arrival of refugee puritans, also known as English Separatists at the time, (and later after the Mayflower Compact would call themselves ‘pilgrims’), went to Pautuxet, renamed it Plymouth, and in the winter of 1621 Massasoit’s Pokanoket council established treaty with the invading arrivals, thereby saving their starving lives.

Historical accounts from a diversity of perspectives are essential to healthy, vibrant democracies so recently published Finding Balance: The History of the Seaconke Pokanoket Wampanoag Tribal Nation is a long overdue accounting of local history from the perspective of Pokanoket Wampanoag people from Massasoit descendant via his daughter Aimee, historian and artist, Deborah Spears Moorehead.

“Because it is our way, my ancestors were acting normal, full of hospitality, kindness and goodness when the peace treaty was signed,” said Spears in an interview. “Once the Pilgrims knew they could survive and thrive on our homelands they disregarded the peace treaty they made with Massasoit when he died fifty years later. The Pilgrims disrespected and undermined Massasoit’s son, Wamsutta, who was next in line for his father’s leadership authority, ultimately poisoning him.”

Events commemorating the Pilgrims landing are being planned by Plymouth400TMINC.

“Plymouth 400, to me, is the people that came here – we call them the invaders – they came here 400 years ago, it’s their way of documenting that they were here for four hundreds years, and that they are documenting their survival and their success in their dominance.”

Educator of Native American studies, Mara De Freece Lawrence, PhD describes ‘Finding Balance’ as:

“The oral traditions of a people for whom the spoken word is a covenant between the natural world and the spiritual for which there is no equivalent context among the non-native people.”

Spears Moorehead also draws on primary documents her grandfather, William Elmer Smith (1879-1929), left in a wooden chest including a vast array of family and business documentation, pictures, and genealogy of their family, the Annawan and Massasoit’s people.

“He died sixty-four years before I received his ledgers, this box, and still the content of his wooden chest was meticulously put away for his family. It protected our identity while also saved proof of our heritage as Pokanoket Wampanoag people.”

What inspired Spears Moorehead most to write her family’s story was her grandfather fatally catching pneumonia at forty-nine while volunteering his carpentry skills building the Seekonk Free Methodist Church. A devoutly Christian man, Elmer Smith’s last will and testament was also included in the wooden chest.

“When people killed my ancestors in the name of God and Christianity, that made it hard for me to believe that Christianity was good, and of God. But then, as I was taught more about Christianity, I realized that all humankind sin, and that is why we need a savior to take away our sin in order to be with God.”

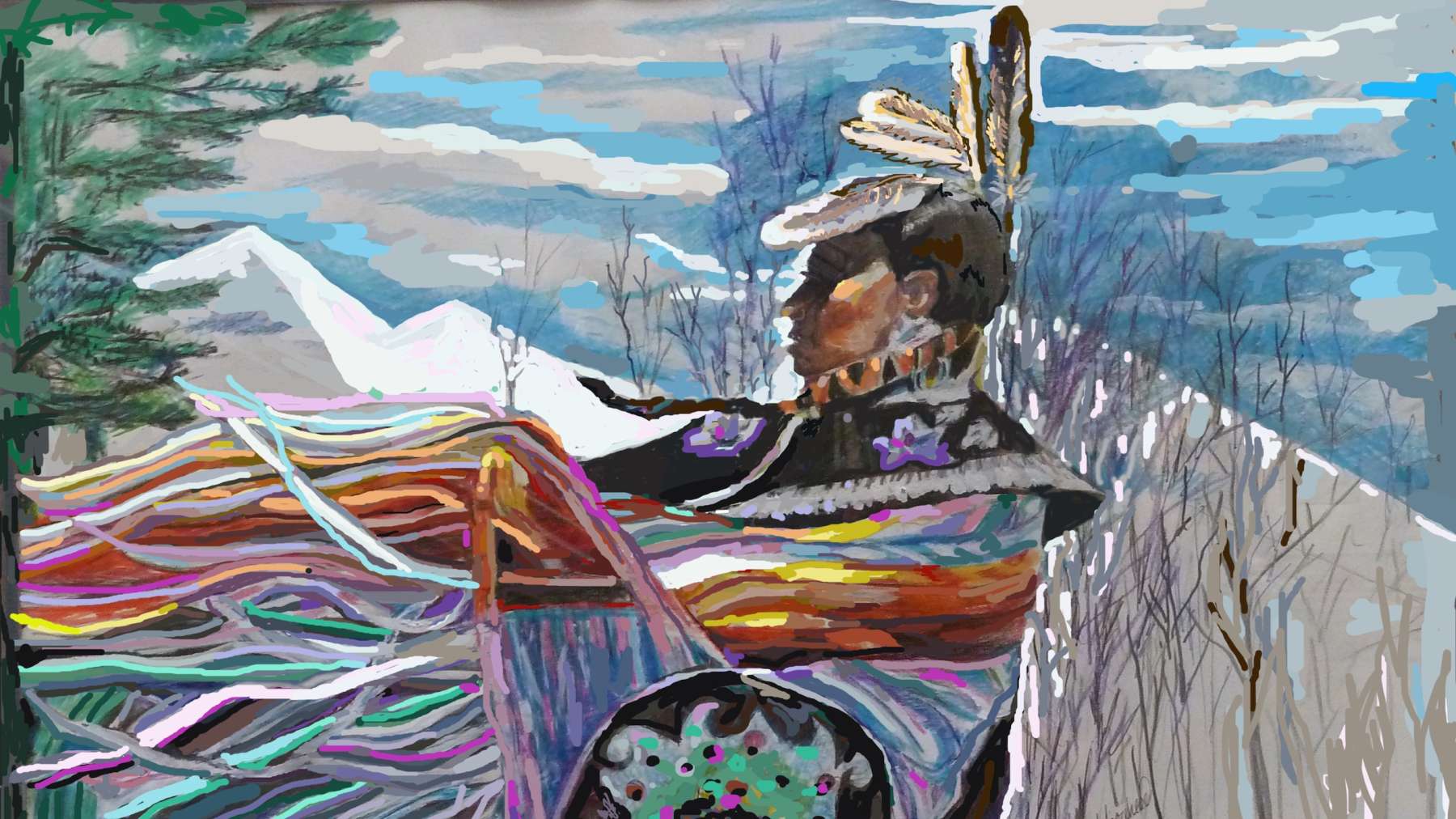

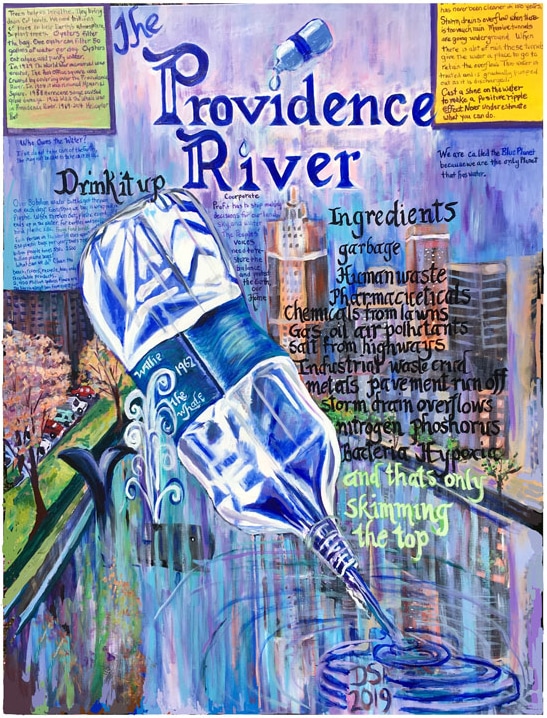

As wife, mother, grandmother, community-builder, historian, academic, painter, sculptor and storyteller, writing ‘Finding Balance’ was one of the many ways Spears Moorehead contributes to keeping Pokanoket Wampanoag culture strong.

“The Spirit of the Creator is to share and love one another, however we are taught through a capitalistic view of society to make as much money and profit as possible, without considering others or the results of the damage done to the environment.

“Domination, hegemony, making sure that one stays on the bottom, so that the other one can stay on the top. For Native People, in our traditions and our cultures, everyone is equal. That’s why we always sit in a circle, because no one needs to be up front, and saying that they have all the answers. The answers are negotiated in a council-like setting.

“The Spirit of the Creator would want you to share and love and help and realize you’re only on this earth for so long. I understand wanting to gift something to your children, but how much do you really need before you realize you’re okay?

“If that balance is so off that it destroys the environment – then what are you really gifting to your children? Enough money so they can live in parts of the world where the environment is safe? But it’s getting to the point where there’ll be no place in the world that’s totally safe.

“That’s why I like the word, ‘reciprocity.’ Humans need relations with others. And how you have a good relationship is you give and take. It has been 400 years since European contact with my people on our homeland and it has been take, take, take from us Indigenous people and 99 percent of our homeland has been taken away.

“Colonization techniques continue to divide the bands within the Wampanoag nation to keep us from uniting, but we are less than one per cent of the population!

“Are we really still seen as a threat? Or is it that we are suppose to assimilate so that no-one ever feels the guilt of all the wrongs done to us?”

The Plymouth400 celebrations include a traveling exhibit on the history of the federally- recognized Mashpee tribe, and a similar organization based in the United Kingdom, Mayflower400, features a UK tour of wampum belts recently made by local Wampanoag, including Spears Moorehead who assisted after being asked to at a recent pow wow.

“Mashpee and Aquinna Wampanoags have worked extremely hard for decades to have their federal status for which they deserve. There are descendants of Massasoit (Pokanoket Wampanoags) incorporated into the Mashpee and Aquinna tribes after King Philip’s War.

“My band, the Seaconke Pokanoket Wampanoag Nation, we haven’t received federal recognition yet. Every time we apply, they change the rules. You spend 25 years trying to meet one criteria and just when you meet, they change it.

Most recently the Pokanoket Wampanoags understand that in order to be considered for federal recognition they have the burden of proof to show the federal government where their name was publicly displayed as a united tribe specifically in the year 1900, or prove why the tribe was not displaying their unity in public view.

“It’s just what they do. It’s psychological warfare. They really don’t want us to ever come back together again. Because they saw us Pokanoket as such a threat: Massasoit’s children, his son, Metacomet, were the ones they fought the war against. We couldn’t call ourselves Pokanoket after the King Philip /Metacomet War, because there was bounty on the head of any Pokanoket. For safety, generations of people of the Pokanoket called ourselves just Wampanoag.

“Today, as Massasoit’s tribal community, the Pokanoket, we are land less. Mega-million dollar universities, corporations and land trusts privately own our sacred homelands and are not willing to part with them, and the funding to give our story a voice never seems a priority.”

The Brown University brand projects an image of caring about climate restoration and restorative justice, yet still maintains hegemony over sacred historical sites including Metacomet’s seat at Mount Hope that the university was gifted in 1955.

“Where does the greed end, and when will the Earth be protected? When will Indigenous people and their rights be protected? Indigenous people live as stewards to the land. When will European Americans get it? Is it too late? When will the greed be enough? When will they return our land and compensate, respect Indigenous ways of reciprocity? When will communities protect the land, air and water, so that we can all live healthy?”

Spears Moorehead says Plymouth 400 shows:

“It hasn’t really changed. It’s the same people still dominating the conversation. Their celebration continues the centering of invading European American dominance.”

“Maybe they don’t know about us; we had to be silent for so long. It’s easy for them to say we don’t exist because then they wouldn’t owe us anything – that would require reciprocity.”

Like so many Indigenous people the world over, the people of the Seaconke Pokanoket Wampanoag Tribal Nation have had to be careful of what they say in public to protect the survival and safety of their people.

“I wrote this book because this was the first time it was safe for us to even speak our side of the story. All the primary documents that explained what happened before my book were overwhelming represented by non-native people, the invaders, so it’s all biased against us, which perpetuates and is still ongoing.”

Growing up, Spears Moorehead’s persistent questions to elders “seemed to make them painfully uncomfortable” – which provides insight to the significant obstacles she surmounted in not only facing, but then also documenting and publishing the thorough account of her people’s history.

This culture of silence among elder generations around what it means to be Native American was also recently discussed at a Warrior Women: Celebrating Indigenous Women panel hosted by Providence Cultural Equity Initiative.

“I couldn’t understand why we weren’t supposed to tell no one. They’d say ‘you’re Indian’, and I was like “yeah, but why is it so bad?” shared Michelle Singing Voice Johnson.

In Finding Balance Spears Moorehead recalls a Native Alaskan woman explaining why she kept what she knew to herself. Her children had been whipped for speaking their native language on the school playground.

“Maybe you turned it around now…but I don’t really know if you have, so I don’t teach nobody nothing, no language, no songs, no nothing. I don’t want no kids to suffer.’”

Erasures of Native People’s cultures continues across the globe at an alarming rate, especially alarming at a time when with every developing natural disaster there is ever-increasing awareness of the necessity to elevate cultures that guide, celebrate and honor the spirit of reciprocity in relationships and balance with nature.

“If we can do what is right, then there has to be reconciliation,” shares Spears Moorehead. “If they can learn to respect what people believe and not see everything that other people believe as evil, then there could be reconciliation. If they would stop putting down cultures that they don’t understand, that would help the whole human population to be able to come together easier.”

All art this page (c) Deborah Spears Moorehead, used with permission