Judge’s decision reveals why all Wyatt ICE detainees are being given bail hearings starting tomorrow

“The fact that … the government has not undertaken any real effort to ascertain the underlying medical conditions of the detainees in this case arguably could [rise] to the level of conduct that is both deliberately indifferent and objectively unreasonable.“ Tomorrow, ICE detainees at the Wyatt Detention Facility in Central Falls will begin bail hearings and possibly be released, due

June 2, 2020, 6:57 pm

By Steve Ahlquist

“The fact that … the government has not undertaken any real effort to ascertain the underlying medical conditions of the detainees in this case arguably could [rise] to the level of conduct that is both deliberately indifferent and objectively unreasonable.“

Tomorrow, ICE detainees at the Wyatt Detention Facility in Central Falls will begin bail hearings and possibly be released, due to a decision from United States District Court Judge Mary McElroy. At least five hearings will be held each weekday until bail requests are exhausted. At these hearings, “the parties will address all relevant considerations, including any special characteristics of the detainee relative to medical risks, his criminal and immigration history, the danger if any to public safety presented by the release of that particular detainee, and the specific petitioner’s plan for release.”

What follows are explanatory excerpts from Judge McElory’s decision, which explains in some detail why:

The issues presented by this case are at the confluence of two constitutional doctrines applicable to civil detainees. First is the indisputable principle that the government has the obligation to safeguard the physical security of those it incarcerates, to protect them from known risks. The authorities need not know of a precise risk, or foretell precise harm, but they must act to forestall a substantial risk of harm of which they are aware. Second… the Fifth Amendment’s due process clause provides protection as well. The due process clause protects a pretrial detainee against “excessive force that amounts to punishment.”

The petitioners here are held by the government for alleged violations of immigration laws. As such, they are civil detainees who are “entitled to more considerate treatment than a criminal detainee, whose conditions of confinement are designed to punish.” They are entitled, as a matter of substantive due process, to “safe conditions of confinement,” and the government has the obligation “to provide reasonable safety for all residents and personnel within the institution.”

It is clear from the evidence produced thus far, and the government’s own submissions, that there is at the very least a clear question of substantial risk of serious harm from contagion by the COVID-19 disease, under current conditions at Wyatt.

“Congregate living, such as nursing homes, cruise ships, aircraft carriers, and that at Wyatt and other detention facilities and prisons, magnifies the risk of contracting COVID-19.”

Wyatt, like many other facilities, has been endeavoring to modify its conditions to meet the current threat. It has instituted a number of new procedures in response to the health risk. However, even assuming the Respondents’ factual assertions about conditions at Wyatt are true – and many have been disputed by the petitioners – there remains a substantial risk of serious harm to the petitioners. The number of cases at Wyatt, in spite of precautionary efforts that have been made, has been steadily increasing. The number of detainees currently held there is 578, requiring some inmates to occupy cells with at least one other – a situation that makes “social distancing” impossible. Wyatt relies on double-celling and the 5’ x 9’ size of cells is clearly too small to guarantee at least 6’ of separation between cellmates at all times.

Mealtimes are congregate, with “1-2 detainees at a 4-person table.” The government provides no information about the size of the table, but it is extremely unlikely to be 6’ x 6’, making social distancing impossible during all meals. Further, detainees are required to stand in line to receive meals, a process which also makes social distancing impossible. And, of course, inmates are eating, an activity that precludes them from remaining masked. Exercise time in the yard is congregate; showers, except for quarantined detainees, are congregate. Staff are mingled throughout the institution; there appears to be no attempt to limit the number of different staff with whom detainees come into contact, and staff clearly go in and out of the institution and mix to varying degrees with family and the public.

The Court has inconsistent information with respect to the procedure for accepting new detainees. The government represented to the Court that new detainees were quarantined for 14 days upon entering the institution. The status report indicates that period is 8 days, within which time the new detainee is tested twice; if both tests are negative, he is moved to general population. The period of contagion, however, is uniformly agreed to be 14 days, and, in addition, there is a high rate of false negative tests.

The consequence of infection is thought to be especially severe for those with “known vulnerabilities,” such as age, pre-existing respiratory or cardiac conditions or disease, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and other maladies. Yet there have been many deaths among persons who have no known pre-existing risks. In addition, the ICE immigrant population almost by definition includes undocumented persons, a population that has historically received inconsistent medical attention, so there may well be exacerbating physical conditions among detainees that are simply undiagnosed.

ICE has been under directives to identify all detainees falling into specific risk categories for nearly two months. Peter Berg, the Assistant Director of Field Operations of ICE, on April 4, 2020, listed risk factors and specifically directed Field Office Directors to determine which of the detainees in their area of responsibility met any of those criteria.

It is clear from even a brief review of the medical records provided by the government in response to this Court’s order that this has not been accomplished for the detainees in this case.

Most, if not all, detainees brought to the Wyatt facility arrive there without any medical records. Records seem to begin at the date of intake at the Wyatt detention facility.

Most are reliant on an oral history given by the detainee upon his arrival and a cursory medical examination. These facts alone, when added to the failure to conduct a thorough medical evaluation – by a doctor and with appropriate diagnostic testing – of each detainee means that the government does not actually know which detainees have underlying medical conditions that put them at extreme risk should they contract COVID-19.

Even more disturbing, the records that do exist reveal a number of potentially high-risk individuals who the Respondents have not identified in their filings as being especially vulnerable.

For example, a very cursory examination of just a handful of medical records shows that the government records the height and weight of every detainee but fails to calculate whether the Body Mass Index (BMI) denotes obesity, a high-risk category. Several detainees report, and intake nurses note, things such as a history of hypertension. Some include notes of medications these detainees are taking but, again, these individuals have not been labeled “especially vulnerable.” At least one detainee, also not identified, is an insulin-dependent diabetic.

The Wyatt Detention Facility is in Central Falls, Rhode Island. Central Falls has the highest per capita rate of Covid-19 infection in the state. As of May 31, 2020 Central Falls had 806 confirmed cases which translates to an infection rate of 3,980 per 100,000 residents; that rate is more than double the state average. The fact that several months into this pandemic and with widespread infection in the detention facility and surrounding community, the government has not undertaken any real effort to ascertain the underlying medical conditions of the detainees in this case arguably could [rise] to the level of conduct that is both deliberately indifferent and objectively unreasonable. Indeed, the lack of that reliable and complete identification has led here to hearings for all detainees, not simply a subgroup.

Thus, the conditions at Wyatt, combined with the fact that COVID-19 is present in the institution, constitute emergency circumstances for every detainee housed there.

In order to prevail in their quest for bail hearings the petitioners must show that they have presented a substantial claim of constitutional error, and exceptional circumstances. That burden is carried by the conditions that Respondents concede are present in the Wyatt detention facility. These conditions, in the aggregate, combined with the fact that COVID-19 is present at the Wyatt Detention Center, present a case for a substantial claim of constitutional error and present facts which may lead the Court to conclude that their continued detention under these circumstances presents a substantial risk of serious harm or death.

I therefore ORDER that the petitioners will be afforded individual bail hearings, beginning Wednesday, June 3, 2020.

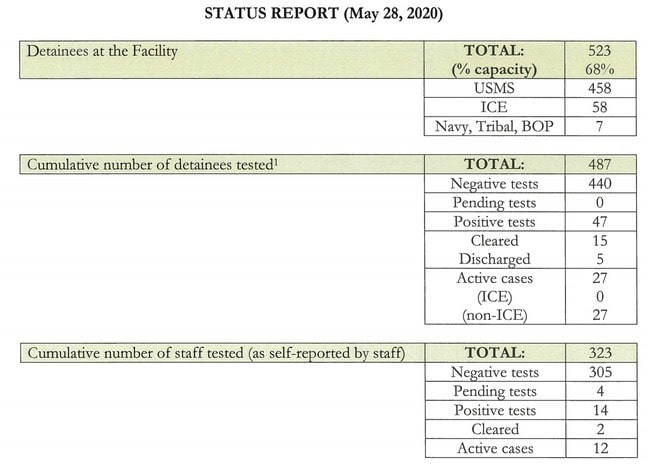

Here’s the latest Wyatt Status report on COVID-19 in the facility: